Leonardo to Matisse at The Met

- Inspired Original

- Dec 18, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2023

Master Drawings from the Robert Lehman Collection

NEW YORK—Artistic endeavors usually begin with a drawing. As if taking a cue from “the first art historian,” Giorgio Vasari, who deemed drawing the foundation of all art forms, The Metropolitan Museum of Art is exhibiting some of its most prized drawings in “Leonardo to Matisse, Master Drawings From the Robert Lehman Collection,” until Jan. 7, 2018.

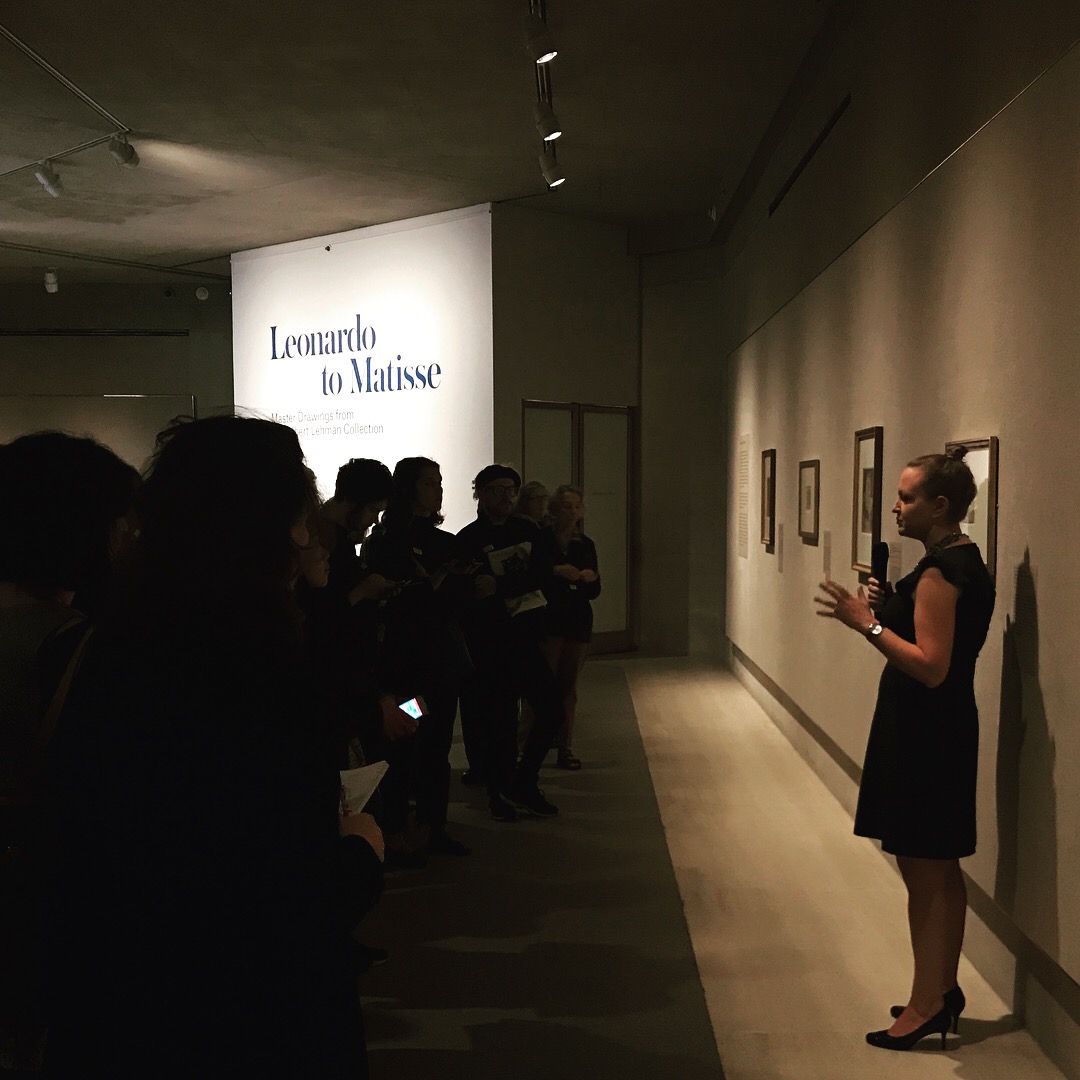

It is the first time the museum has “pulled the greatest hits from the collection of 750 drawings,” said Dita Amory, curator in charge of The Lehman Collection, at a press preview on Oct. 2.

The exhibition is a mini-survey of Western art in 60 drawings, distilled through the discerning taste of one man—Robert Lehman. Adding to the painting collection of his father, Philip, Lehman bought his first drawings in the 1920s and continued collecting voraciously until his death in 1969. “It’s been said he collected at a pace equivalent to buying two works of art every week of his life,” Amory said. “Although he took counsel from the legendary art historian Bernard Berenson [a Renaissance specialist] and others, Lehman was very much his own curator,” Amory said.

Organized in four sections in the diamond-shaped Lehman gallery, the exhibition begins with 15th-century early Italian Renaissance drawings (including a drawing of a bear by Leonardo da Vinci, and one of the drawings Vasari owned and wrote about in his 16th-century book “Lives of the Artists”). Around the corner proceeding clockwise, these can be compared with their Northern European counterparts from the 15th to the 17th centuries (for example, Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt). The exhibition then transitions to 18th- and 19th-century Italy and France (Tiepolo and Ingres, among others); and abruptly switches to 20th-century impressionism and early modernism (Seurat, Degas, Matisse, and so on).

It’s fitting that Lehman began his drawing collection with rare sheets by Italian Renaissance masters, because it was during the Renaissance that “the function and the status of drawings was really developing,” said Alison Nogueira, the associate curator of the Lehman Collection.

In addition to functioning as workshop tools that artists used to record designs and as stock motifs that could be used in the preparation of finished paintings, sculptures, furniture, and works in other mediums, drawings became works of art in their own right “as expressions of artistic creativity, of the artist’s genius, and personal style,” Nogueira said.

Also “at this time drawings became a medium for experimentation and exploration. So you see artists thinking on the paper,” she said. A case in point is one of the most prized drawings in the collection, a peculiar self-portrait by Dürer, which he made when he was 22 years old. “It reflects his emerging artistic self-consciousness. The way he has rendered his own image with arresting directness was highly unusual at the time,” Amory said.

The self-portrait includes a study of his hand and a pillow, and on the reverse side of the paper, a study of six pillows. “We think of it as a dialogue between the hand and the mind, between mental and physical creativity,” Amory said. A German theologian of the time, Nicolas of Cusa, wrote that the entire character of man is found in his hand. The hand can then be considered as a kind of alternate self-portrait, Amory said.

When artist Burton Silverman looked at the same drawing on a visit to the exhibition on Oct. 4, he said, “I think Dürer is exploring how effectively he could render form with cross hatching. He was a linear artist, if we talk about linear versus painterly. So this is perhaps an exercise in pursuing that affection for the line.”

With artist Edmond Rochat, we speculated whether Dürer was perhaps just doodling on a blank piece of paper. “The pillows fit a contemporary sensibility because they are also relatively uninteresting,” Silverman said. The composition of six pillows in two rows was isolated from any broader context.

Rochat chimed in while looking closely at Dürer’s ink hatchings. “This pillow is not the same as that pillow and those folds and hatch marks are not the same, so Dürer is indicating a different dynamic in each one,” he said.

“Once Dürer tried to draw them, he realized that he didn’t fully understand what he was looking at. In other words, if he is describing it well, then he is understanding it well. I don’t think he was just doodling in his room. He studied very deliberately what he was observing. When I see that Dürer, it is like a theory, but it is not an abstract theory. The drawing is the theory,” Rochat said.

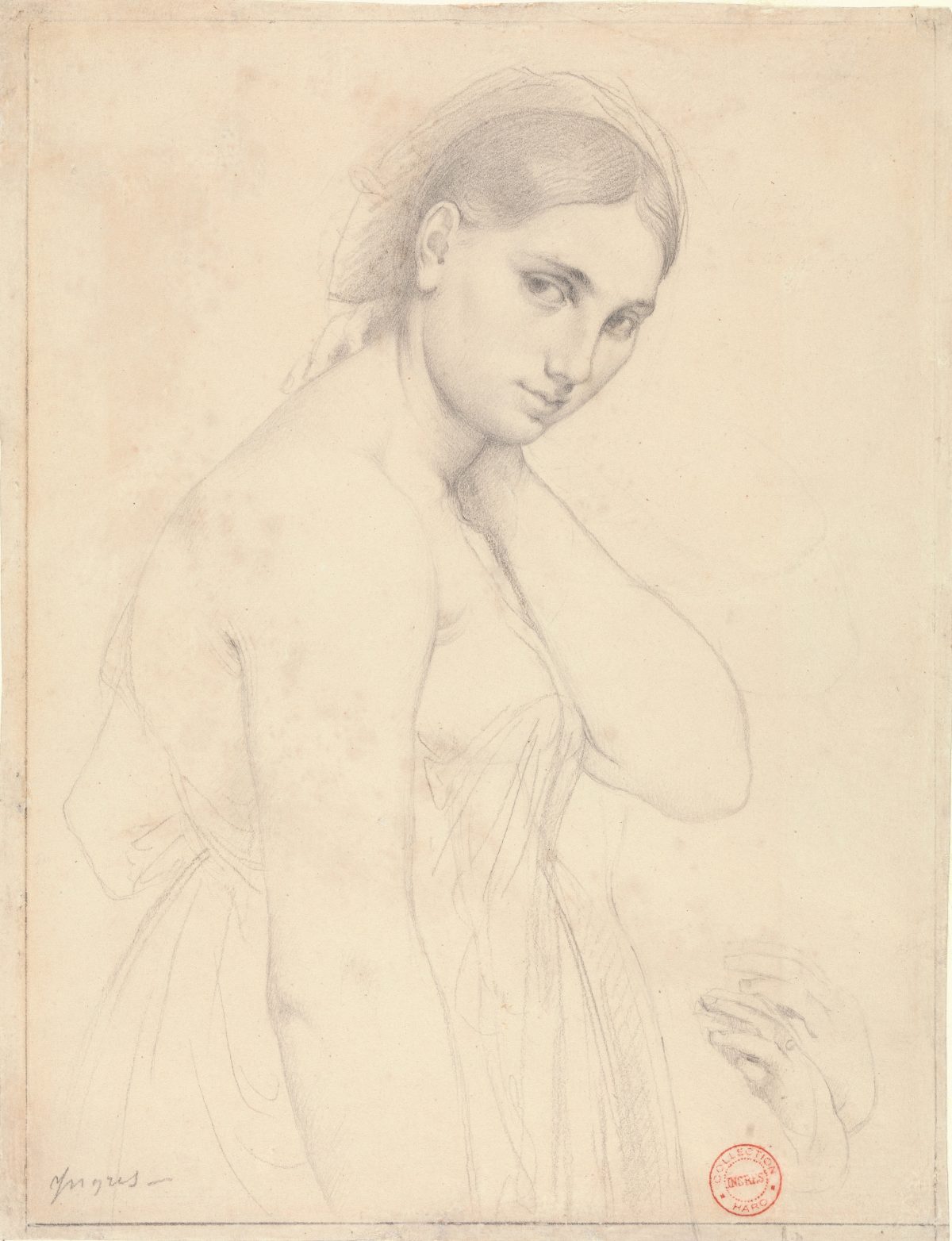

Another drawing that drew much attention was by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), a study for “Raphael and the Fornarina,” the poster child of the exhibition. It is a study Ingres made for his painting with the same title, which depicts Raphael and the baker’s daughter, Margherita Luti (fornarina means “little baker” in Italian).

Ingres admired Raphael profusely. The drawing is an example of an emerging genre in the 19th century in which artists depicted other artists in their studios with their models. Raphael was said to be in love with Luti, and Ingres drew his first wife, Madelaine Chapelle, at the time when he was courting her, to represent Luti. “There is a marvelous synergy between the painting and his relationship to it,” Amory said.

Aside from the delightful anecdotes that give more of a personal context to a work of art, Ingres’s drawings elicited sighs of praise.

“He is drawing a particular woman, but the aesthetic is actually of Greek antiquity. And there is an entire worldview behind that, of what the pinnacle of art should be. There is no way to calculate that, but it is just his awareness of crafting it in that way. She is essentially a Greek goddess. She looks like Athena,” Rochat said.

Silverman added, “What makes his work so engrossing is the combination of those linear qualities in the body of his subjects with the highly evolved tonal areas around the head, which is a device that he used almost throughout all of his drawing. Along with it, of course, was the personality he captured in these small, incisive studies.”

Another of our favorites was a magnificent ink wash drawing by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, which Rochat noted has only three values: dark accents, shadows, and the color of the paper for the highlights. It looks very abbreviated in its execution, but the overall effect feels very full and complete. It jumps off the page.

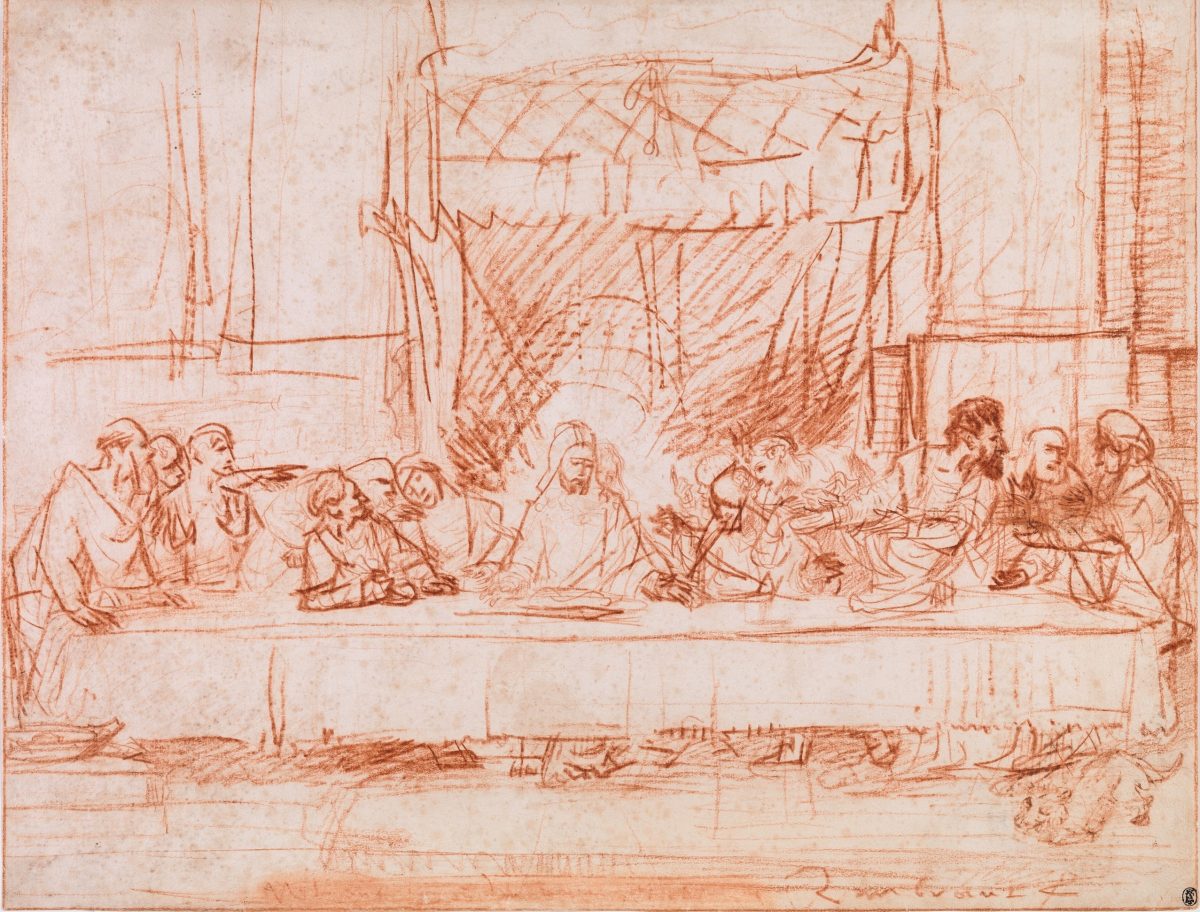

Other favorites included “The Descent into Limbo” by the circle of Andrea Mantegna; a whimsical drawing of men shoveling chairs by the circle of Rogier van der Weyden; a Canaletto landscape; a small self-portrait by Goya; a couple of Degas drawings; and two Rembrandts, including his drawing of da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” which curiously includes a dog.

Contributed by Milene Fernandez

Pure Truth, Kindness and Beauty

It’s a great pleasure to present to you an inspiring story from the Award-winning painter Lauren Tilden. Her painting “Birds of the Air, Grass of the Field” has won the Bronze Award from the NTD International Figure Painting Competition in 2019.

“Working on that painting was a reminder to me not to worry. There is more to life than the issue you are facing at this moment.” – Lauren said.

While contemplating the value of human life, and how precious it is, the artist’s own young daughter became her stand-in, her persona in the painting. Please join us on this wonderful journey to visit Lauren in West Virginia.