Job: Suffering and Sincerity

- Inspired Original

- Mar 20, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 20, 2023

Reaching within: What traditional art offers the heart

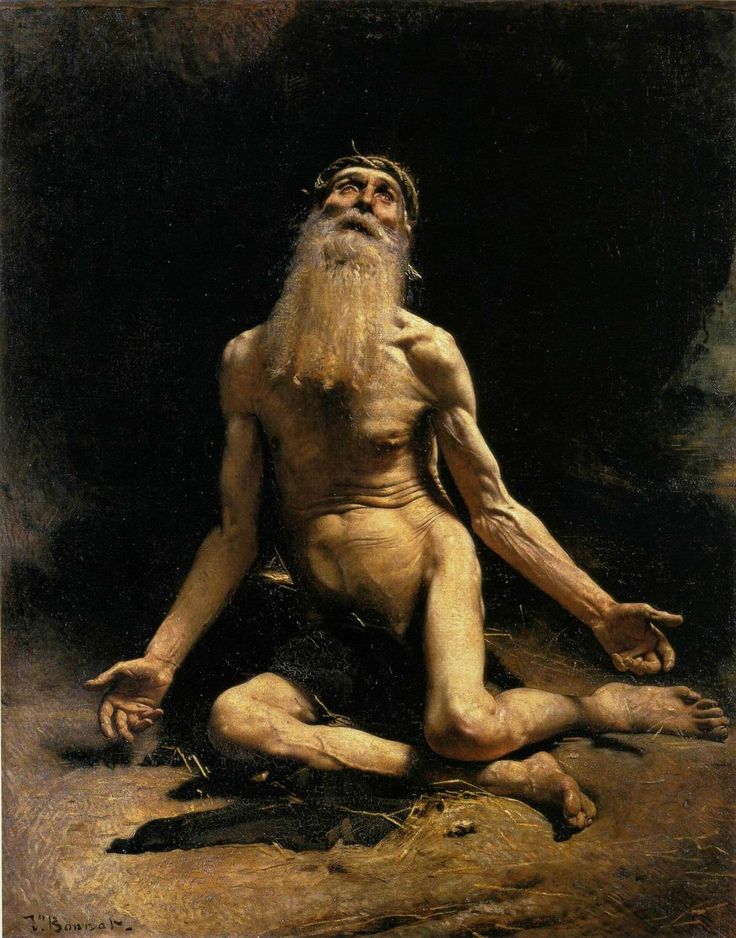

I recently saw Léon Bonnat’s painting “Job,” which powerfully represents the suffering and spirituality of Job. I decided to visit Job’s story in the Bible, and I came to deeply consider my relationship to my own sufferings.

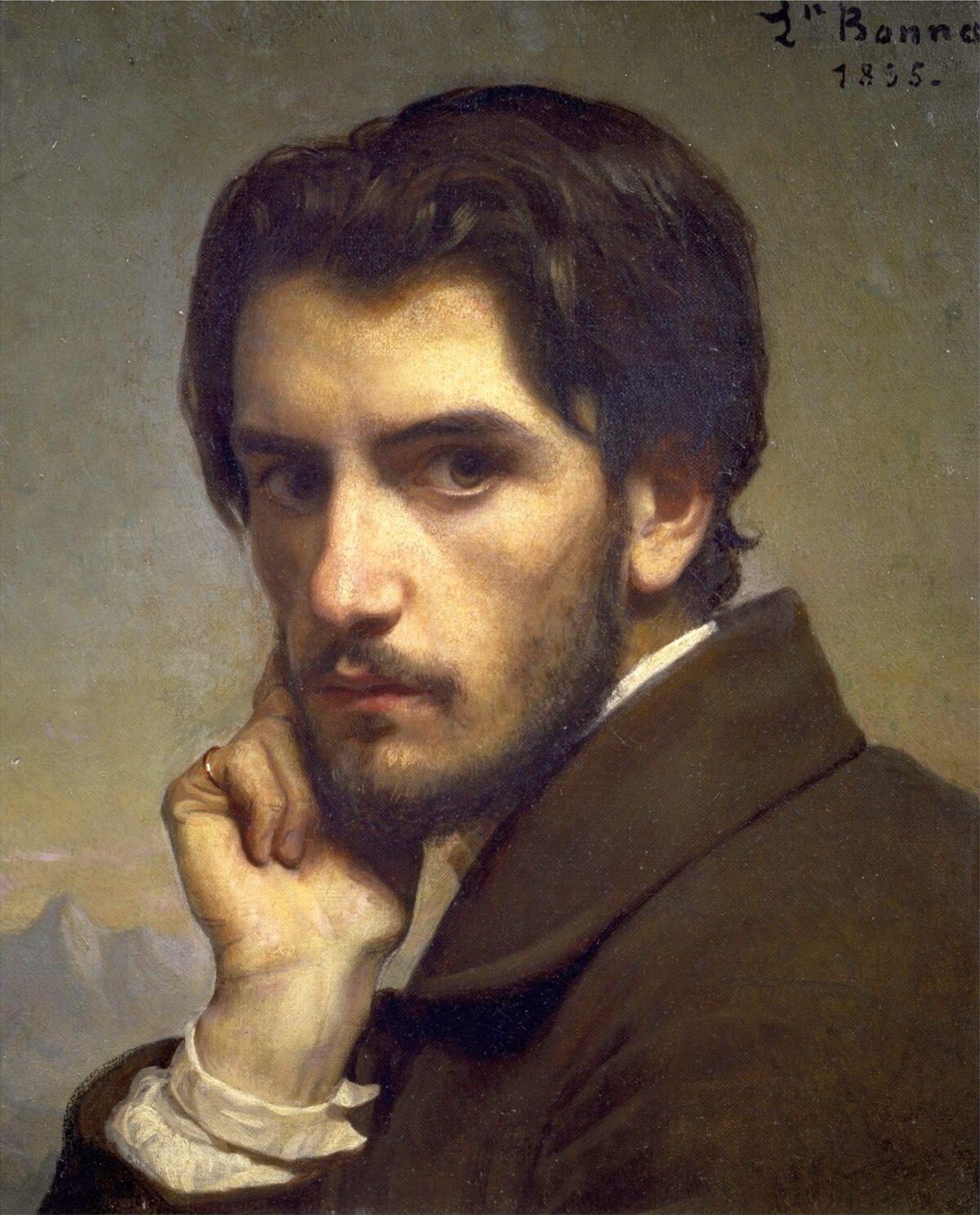

Léon Bonnat

Léon Bonnat was a French academic painter during the 19th and early 20th centuries. He traveled to Spain to study Spanish Baroque art under Federico Madrazo before returning to Paris to study painting at the École des Beaux-Arts, the national school of art in France.

Instruction at the École, however, had become stagnant and abstract. Instructors were no longer teaching methods for creating art but were theorizing about art, and student work was suffering as a consequence.

According to art historian Alisa Luxenberg, “Bonnat saw three cancers within the academic system: partisanship, routine, and entitlement.” Students were often selected to win competitions because of favoritism and persistence instead of talent; they became lazy and felt entitled in an environment that fostered absolute and unvaried instruction.

In 1863, a decree was implemented to reform instruction at the École. Many of the faculty members resisted these reforms. But Bonnat, at this point a practicing artist, signed a letter to Napoleon III that supported the reforms. This signature created tensions between Bonnat and his colleagues.

The debates concerning the reforms were very tense. Artists were potentially sacrificing their future careers depending on what stance they took in relation to the reforms.

Later, Bonnat said this about signing the letter: “That blessed signature is in the process of causing me disagreements with all my friends. Where I only saw a question of transforming [the École’s] studies, wholly to their benefit, they see an act of profound intrigue, and they associate me with people who want to destroy the Institut, the Rome prizes, freedom itself and, consequently, . . . the death of art. It is very serious and I will have trouble getting out of it.”

Despite the tensions between Bonnat and his colleagues, he later became a professor and director at the École.

Interestingly, teaching caused Bonnat to question his original concerns with the instruction at the École. He came to reflect that perhaps being abandoned by his professor was not negligence at all. On the contrary, it was likely part of the training.

In reference to his atelier training, he stated:

“[Art instructor Cogniet] knew that one learns well only what one learns on one’s own, in trying, in seeking. He thought that mutual learning is the most efficient teaching, and finally and above all, he did not want to impose on his students his way of seeing, of understanding, and interpreting life.”

Bonnat endured professional hardships because he remained true to and sincere in his convictions. Yet he also was not dogmatic in his views but open to questioning them, and he came to believe that his greatest education in painting came not in the instruction that was provided but in the sincerity of one’s own efforts.

In 1880, Bonnat completed his painting of Job, after the reforms of 1863 but before he became a professor at the École in 1888.

Job’s Sufferings

Job is a biblical character of the Old Testament whose faith in God is tested due to great suffering caused by Satan. Job’s story is paraphrased as follows from the Book of Job:

Job is a very successful and blameless man who shuns evil and worships God. God asks if Satan has seen Job’s virtue and faith. Satan suggests that Job is virtuous and faithful only because he is successful; take away his success, and his virtue and faith will falter.

God, believing Satan to be wrong, allows Satan to take away Job’s successes. In one day, Job loses his sheep, servants, and children to thieves or natural disasters. Despite this, Job praises God.

Satan returns to God and suggests that Job still praises God only because his body has not been harmed. Satan then causes Job to have horrible boils and skin sores. Job’s wife asks him to renounce God and die. Job refuses and states the importance of accepting the good with the bad.

Three of Job’s friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar arrive to comfort him. At this point, Job curses the day he was born and believes he is living only to increase his suffering. Each of his friends tells him that his suffering must be the consequence of sinful behavior, and each explains God’s justice according to his own understanding.

Job, however, sure of his virtue, comes to question God’s justice. He denounces his friends’ accusations and demands to defend his virtue before God.

God reveals himself to Job and tells him that he, with his limitations, cannot understand the justice of God but must, nonetheless, trust God. Job agrees. God also tells the three friends that they were wrong about God and that Job was right. God was satisfied with Job, because Job is sincere with his questions and concerns. God restores Job’s health, gives him twice as much property as he had before, new children, and a long life.

Bonnat’s Depiction of Job

Bonnat depicted Job naked and alone on a background of darkness. He used baroque contrast of light and dark to illuminate the form of Job in front of the darkness. Job’s head tilts toward the heavens with a pleading look of suffering on his face, and his hands are stretched in front of him with his palms up as if he is preparing to receive something.

Though the composition is a simple one with a single figure, Bonnat arranged the figure in one of the most compositionally stable shapes: a triangle. Job’s head is the top of the triangle, his arms are the sides, and his legs are the bottom.

Why did Bonnat depict Job in the shape of a triangle? Why is Job depicted naked and alone? Why are his hands outstretched? What moment of Job’s story did Bonnat depict?

An Interpretation

I think Bonnat depicted the moment in which God reveals himself to Job. Job has called to God for a face-to-face meeting and God appears. Job receives God’s message with his hands outstretched.

Job is naked and alone because sincerity and honesty are necessary in order to meet with God. Thus, Job is shown in his bare truth as he meets with God.

Maybe this is why Job’s hands are outstretched with his palms up: It is only in his sincerity and honesty, in baring himself, that he is able to receive what God is to provide. Maybe the exposure of his palms is also an acceptance of trust in God’s justice.

This whole event is confusing and turbulent for Job, yet Bonnat depicted him in the shape of a stable triangle. Maybe, despite his sufferings and despite Satan’s role in the story, Job’s soul was always being taken care of by God. In this case, his sufferings may have appeared as unjust and therefore unstable. Is it possible that Job’s sincere and honest approach to his sufferings allowed him a deeper trust in God, a more stable faith?

Enduring Great Suffering

It is simply a fact of life that human existence goes hand-in-hand with suffering. Irrespective of wealth, class, race, or gender, we all suffer. How we deal with that suffering can define who we become as human beings.

It is tempting to want to blame our sufferings on others. It is often too convenient to say that “everything would be different if this one thing would change.” Another temptation is to use our sufferings to elevate ourselves: I am better than others because I suffer more. Both of these positions can lead one away from God.

What might it mean to approach our suffering sincerely and honestly? What might it mean to lay ourselves bare? Before requesting to defend himself before God, Job first questions his own virtue and finds himself true to God’s law. Maybe this act—this introspection—contains within it what it means to approach our sufferings sincerely and honestly; maybe we must be honest with ourselves about our actions and their consequences and ask God the questions that are deep in our minds and hearts.

Like Job, Bonnat had to stay true to what he believed—in this case, what he thought to be good for the arts in France—despite pressure from his colleagues. Bonnat stuck to his guns as a supporter of reform as a means to promote actual instruction at the École, but this threatened his friendships and career in the process.

Despite this, however, he was eventually granted a professorship and directorship at the École. He was blessed through his sincere but plagued efforts, just as Job was later blessed after enduring his sufferings.

To me, Bonnat seemed more interested in sincerely helping the arts than in holding on to insincere views in order to save face, friendships, or his future. Job does the same in the presence of his friends: He approaches God sincerely and honestly, and God reveals himself to Job.

Moving forward, I will do my best to avoid blaming others for my suffering. I will also avoid elevating myself above others because of what I’ve suffered. There’s always someone who has suffered more than I have. Instead, I will share my sufferings with God in an honest and open way so that I may be fortunate enough to experience his blessings. Hopefully, I will have the wisdom to question my assumptions and stay sincere in my heart and mind despite the temptations around me.

Art has an incredible ability to point to what can’t be seen so that we may ask “What does this mean for me and for everyone who sees it?” “How has it influenced the past and how might it influence the future?” “What does it suggest about the human experience?” These are some of the questions we explore in our series Reaching Within: What Traditional Art Offers the Heart.

Eric Bess is a practicing representational artist. He is currently a doctoral student at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts (IDSVA).

Contributed by Eric Bess

Pure Truth, Kindness and Beauty

It’s a great pleasure to present to you an inspiring story from the Award-winning painter Lauren Tilden. Her painting “Birds of the Air, Grass of the Field” has won the Bronze Award from the NTD International Figure Painting Competition in 2019.

“Working on that painting was a reminder to me not to worry. There is more to life than the issue you are facing at this moment.” – Lauren said.

While contemplating the value of human life, and how precious it is, the artist’s own young daughter became her stand-in, her persona in the painting. Please join us on this wonderful journey to visit Lauren in West Virginia.