Ancient Greece Gives Us ‘A World of Emotions’

- Inspired Original

- Oct 4, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2023

NEW YORK—”Think of your father.” These words bring the Greek war hero Achilles to tears when the Trojan king, Priam, requests the delivery of his son’s mutilated body for burial. Achilles had bound the body of Priam’s son Hector behind his chariot and dragged it around the walls of Troy in a fit of rage over the death of a dear friend. Priam then summoned the humility to kneel before Achilles, kissed the hand of his enemy, and made his request.

Upon hearing Priam’s words, Achilles foresees how one day his own aging father might mourn the death of a son. With that realization, his anger transforms into grief. The Trojan king and the unbreakable Greek hero weep together, united by their shared humanity.

The ancient Greeks were well acquainted with representing intense emotions, as Homer elucidated in verse after verse in the “Iliad” (circa 700 B.C.), one of the oldest existing poems in Western literature.

From the very beginning, “the ‘Iliad’ is all about the wrath of Achilles and its consequences. These are not the cute emotions [emoticons] that you get on the iPhone,” said Michael Djordjevitch, a lifelong student of architecture and fellow of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, who currently teaches art history and architecture at the Grand Central Atelier and works for design studio Atelier & Co. in New York.

“Oh, this is a great collection,” he said, looking around the exhibition and interrupting himself mid-sentence.

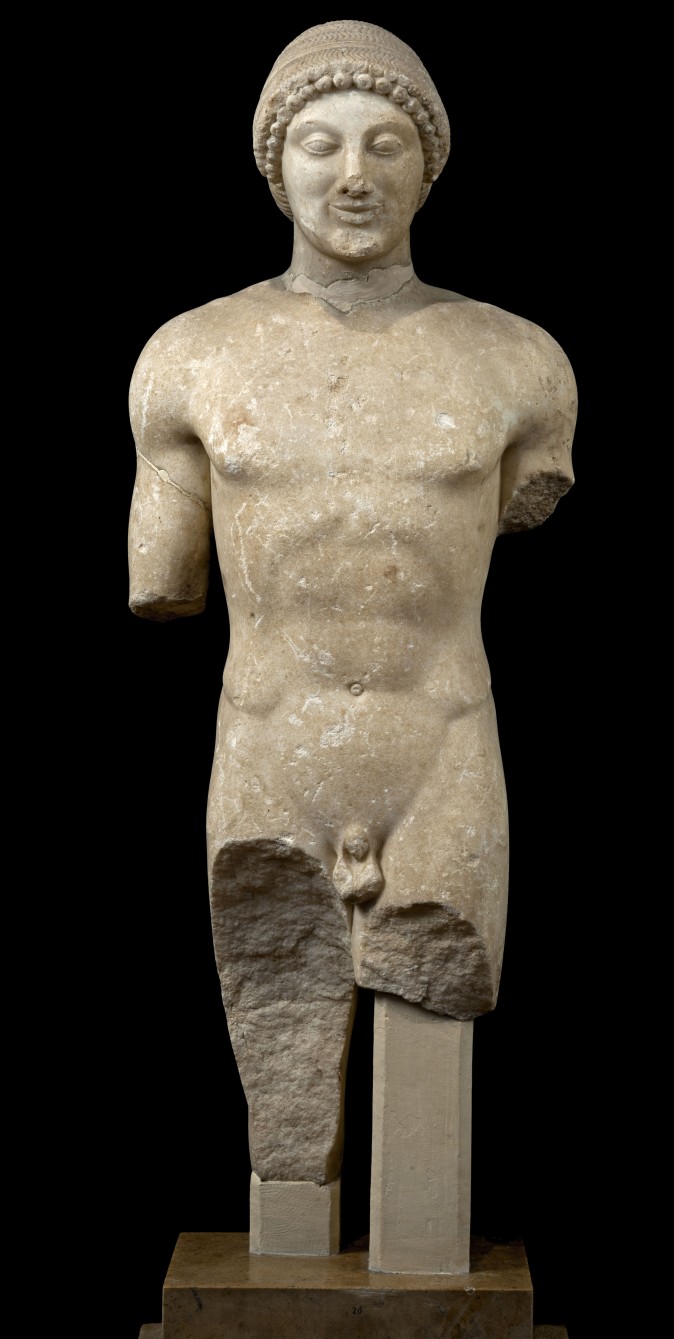

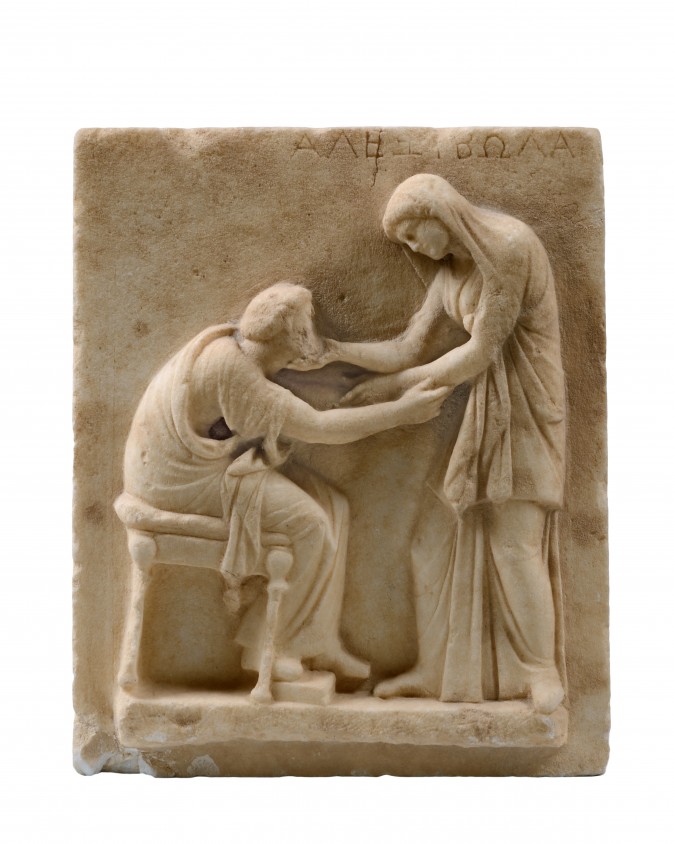

Love, hate, joy, sadness, fear, pity, confidence, jealousy, and hope are some of the emotions reflected in the pieces on display in “A World of Emotions: Ancient Greece, 700 B.C.–200 A.D.,” at the Onassis Cultural Center New York (OCCNY) until June 24.

We do not really know how the ancient Greeks felt, but their literature, philosophy, and artifacts show us how they represented emotions. Each of the more than 130 pieces on display (from leading museums, including the Acropolis Museum, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, the Louvre, the Vatican Museums, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art) tells a story that helps us understand our own.

That’s the hope of the scholars who organized the exhibition—Angelos Chaniotis, professor of ancient history and classics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey; Ioannis Mylonopoulos, associate professor of ancient Greek art at Columbia University; and Nikolaos Kaltsas, director emeritus of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

It’s an easy hope to see fulfilled. Ancient Greek culture—its art, literature, and philosophy—has long proven its universal value, transcending time, ethnicity, and geography.

The ancient writers “understood that emotions necessarily involve judgments and beliefs. … In a word, emotions are profoundly rational,” wrote David Konstan, professor of classics at New York University, in the exhibition catalog. “To be angry, you need to make a judgment about the motives of the other person; if you change your view about these, then the emotion changes as well. Emotions require thinking, and thinking of a very human kind. The ancient writers understood this very well.”

King Priam was able to persuade Achilles by asking him to think. Through discernment, rage turned into grief. It’s the same for positive emotions. “Our love for our friends is based on an appreciation of their good qualities, which may include practical benefits and entertaining companionship, but in the best of cases is elicited by what we perceive as their virtue,” wrote Konstan. Our decision to love somebody is based on moral values and judgments; it’s not just a matter of “chemistry,” he added.

The ancient Greeks developed some of the earliest known theories of emotions. They understood emotions as powers and as divine beings. In a pantheon of more than 30 deities, Ares, for example, is the god of war and violence, while Aphrodite is the goddess of love and beauty. Each god and goddess is associated with their own cocktail of qualities and emotions.

“The ancient Greeks were especially interested in the convulsive emotions associated with war, with large-scale human conflict and its intense liminal experiences,” Djordjevitch said. “The whole of ancient drama tends to be about what happens when you cross that threshold, such as vengeance, and emerge in a new and dangerous realm.”

For example, in “Oresteia,” the Greek trilogy of tragedies, “Clytaemnestra clearly deserved to be executed for the murder of her husband, but it shouldn’t have been her own children who killed her. Greek culture is very much focused on these liminal situations. That’s why it’s so fascinating to us, because they represent a situation where the human is encountered in its inhuman moments,” he said.

“Drama intensifies the everyday to reveal the deeper dynamic that lies beneath and basically structures the everyday. To be a civilized society, all of these liminal emotions have to be kept in check, but they are still real, so you can’t pretend they are not there,” he said.

The ancient Greeks built temples that not only served as spaces for ritual and worship, but for acknowledging and thinking about emotions.

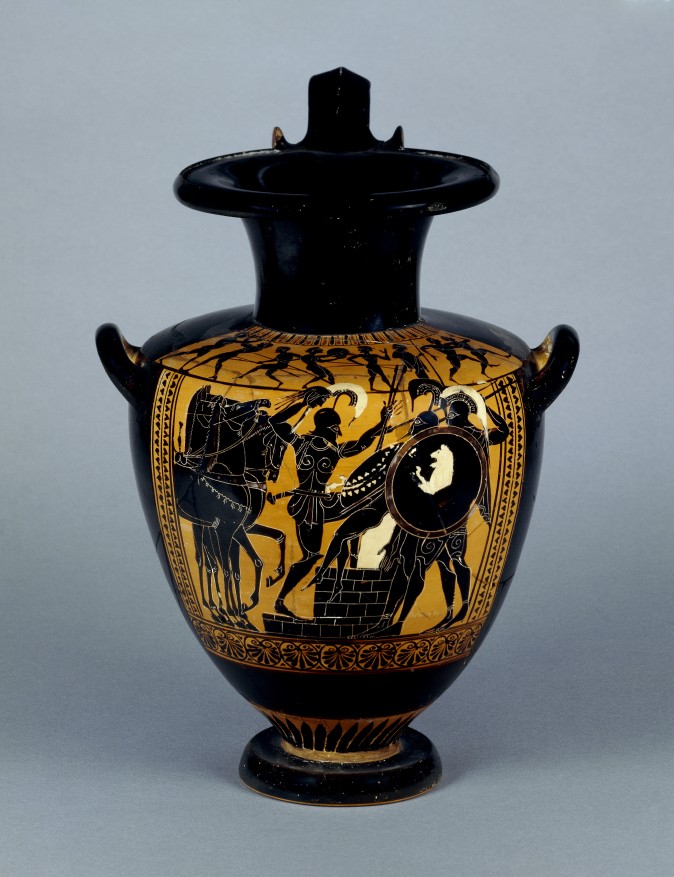

When we see the gory details depicted in ancient Greek pottery—for example, a jealous wife killing her own two sons, in the myth of Medea—and other scenes of mutilation, rape, near human sacrifice, or chaos, we may assume that the ancient Greeks were generally a violent lot. Yet their manner of interacting with each other in daily life was most likely far more peaceful, because they created the space and time to be able to contemplate their emotions through watching those comedies, satires, or tragedies, or through worshiping in temples.

The ancient Greeks developed some of the earliest known theories on emotion. The philosopher Aristotle examined about a dozen emotions, organizing them into pairs, in his treatise on the art of rhetoric. His famous definition of tragedy explained the healing effect of watching tragic plays.

“Achilles only appears before us as fully human when Priam reminds him that he too has a father who will grieve over him. That moment is the catharsis of the ‘Iliad,’ when everybody listening is weeping,” Djordjevitch said. “The ultimate, macho, bloodlust Achilles warrior is suddenly humanized. … That is a fabulous testimony to the spiritual depth and breadth, and emotional maturity, of a culture.”

Catharsis is the whole purpose of tragedy as explained in Aristotle’s “Poetics.” “The whole body-politic participates in purging these emotions by having them represented in a concentrated, controlled, artistic way,” Djordjevitch said.

“The classical as Classical sublimates and basically takes the emotions to a place where they are barely evident to the casual viewer. There’s an intensification, rather than an increase, in the degree of external expression. That’s the very definition of the classical. Everything seems nice until you pay attention, and then you notice the deep emotions,” Djordjevitch said.

At first glance, a terracotta vase shows beautifully delineated figures, composed harmoniously. But on closer inspection, a severe drama unfolds of, for example, Achilles ambushing and murdering the Trojan prince Troilus.

Achilles reminds us that even a hero is fallible and therefore subject to nemesis and retribution. The pieces and the stories associated with them in the exhibition remind us of all the emotions that the ancient Greeks called divinities.

“The Athenians built a temple to ‘Nemesis’ near their great victory at Marathon. It’s not just about ‘oh ha, ha, look at you Persians, you were done in by your hubris.’ It also reminds them that Nemesis follows Hubris, and is a permanent part of their sacred landscape. That degree of self-awareness is the beauty of the ancient Greeks,” Djordjevitch said.

Contributed by Milene Fernandez

Pure Truth, Kindness and Beauty

"When your heart is unmoved, you will see the truth and reasonable way to face any situation."

Join us on this inspiring journey to visit the artist Loc Duong in Vietnam as he shares his amazing experience while creating “Unmoved.”

His first-ever oil painting makes many people feel at peace and won the Humanity and Culture Award in the last NTD International Figure Painting Competition.